Polar (B)ear Tag:

Adventures in designing for the Arctic

Two polar bears exploring the remains of a whale harvested in last year’s hunt. Photo Credit: Elizabeth Kruger

As I was speeding across the tundra on a snow machine, straining to keep a mother polar bear and her two cubs in sight, lit only by the twilight of early afternoon in January outside of Utqiagvik (UUT-kee-AHg-vik) Alaska, it occurred to me that this was the last place I expect my career as a mechanical designer to take me. It turns out, when someone asks if you want to help save polar bears, there is only one right answer.

Just over 3 years ago I was living in my van, traveling around North America when a good friend of mine, Joerg Student, reached out to see if I had any interest in working on a project for World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Joerg and I had worked together for years, as both colleagues at the design firm IDEO and collaborators on wild kinetic sculptures with the Foldhaus Art Collective. I had moved on from IDEO but heard through Joerg about their collaboration with the WWF on a workshop in Anchorage, AK that would bring together scientists, engineers, designers and Indigenous people to figure out the best replacement solution for the tracking collars that polar bear researchers currently used. I was not lucky enough to attend, but when Joerg returned from Anchorage he told me it was one of the most fulfilling workshops he’d ever lead. Clearly the subject matter was something special, but more than that, he was touched by the respect that both the scientists and the Inuit had for the animals. While they shared a common goal of trying to help the bears thrive, they didn’t necessarily align on the correct approach. That’s where the design thinking methodology pioneered by IDEO came into play; it forced people to remove mental barriers and to temporarily suspend the limitations of reality. This concept can be shockingly hard for scientists and engineers, but it gave everyone a chance to approach a problem from a new perspective.

Joerg leading the workshop for WWF in Anchorage, AK. Courtesy of IDEO

The Inuit have a deep respect for the animals and as such feel that they should be disturbed as little as possible. One hunter said that the collars feel disrespectful to the bears and that they are unsightly and unsettling to him. What they want is a less obtrusive solution that doesn’t come with the overtones of “taming” a wild animal. Scientists on the other hand clearly need the data provided by the collars to better understand bear behavior and the effect that climate change is having on their ability to survive. But the collars still leave blank spots in that data due to a few key flaws: they won’t stay on male bears (their necks are too big relative to their heads), they are a nuisance to the bears, the release mechanisms often fail and they just break a lot!

Brainstorming concept sketches from the workshop. Courtesy of IDEO

What the world needed was the Polar (B)ear Tag, a polar bear specific ear tag. Obviously when Joerg asked if I wanted to do the mechanical work the answer was yes! With Elisabeth Kruger at WWF spearheading the effort with partners Michelle St. Martin and Ryan Wilson at US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) providing insight and guidance, various IDEO folks providing a sounding board and the team at Misty West work with the electronics and software, we set about creating a new tracking device that would allow scientists to remotely monitor bear behavior in the wild for an entire year.

The first step was to figure out the guts and brains of the device. Misty West did a deep dive on different satellite, battery and processor technologies to assemble a system that would perform in the extreme environment of the Arctic. Given that batteries function poorly at low temperatures, communicating with satellites requires a lot of power, and that the device needs to be as small and light as possible they had to do an enormous amount of testing and validation of every component that they wanted to put in the tag. Honestly it borders on miraculous that they found a combination that works at all. The last major technological hurdle was to model an antenna that would reach space and not break off. Once again, Misty West proposed a clever solution to allow us to embed the antenna within the bulk of the device where it is protected during its rough and tumble life on a bear’s ear.

While Misty West sorted out the hard stuff, I focused on how to ensure that the ear tag would stay on for at least a year and then eventually fall off all by itself. Enter Andre Labonte! Andre is what you might call a Salty Dog: he’s spent his entire life around the ocean and for decades has crafted specialty time-released fishing tackle. I came across his ancient website while looking into a process called galvanic corrosion and was able to get him on the phone from New Zealand a few weeks later. We talked about how polar bears are classified as marine mammals and spend a good amount of time in the salty waters of the polar seas. He normally makes timed releases that last 2-3 months in warm waters, but because the reaction happens much slower at low temperatures, he thought he could come up with something that would last the 2-3 years we needed. Leveraging Ryan at FWS, we were able to get Andre enough information about salinity in the Chukchi Sea, average air and water temps, and a spitball estimate of how much time a bear spends swimming. Given that the goal was to ensure that the tag fall off eventually, it gave us a pretty wide margin for error and Andre’s initial calculations were promising enough to merit kicking off longer-term tests.

Checking the fit of the first form factor prototype on Lyutyik’s ear.

Checking the fit of my head in Lyutyik’s paw.

At this point we had a fuzzy idea of all the major components, and it was time to package them to fit on a bear’s ear. Michelle had been working in the background, keeping tabs on all the captive polar bears around the country, and in mid-December of 2018 she called me to see if I could get myself to the Anchorage Zoo by the 2nd of January. Lyutyik (LyOO-tee-ik), their 1,100 pound male, had been limping and they wanted to sedate him for a medical checkup. Not wanting to miss this opportunity, I crammed to get a prototype hashed out, 3D printed it, and made my way to Alaska in the dead of winter. When I met Elisabeth, Michelle and Ryan at the zoo, the veterinary team was waiting for the tranquilizer to take effect. Once Lyutyik was soundly asleep we were allowed to enter the veterinary examination enclosure. It’s hard to describe how imposing these creatures are, even when they are thoroughly knocked out. Over the course of the next hour I helped the vets roll him over to collect semen samples for a captive breeding program and do the medical exams they had planned; then they gave me until he started stirring to learn about his ear. I measured every aspect of it. I tried and failed to take a mold of it. I felt how stiff it was. Finally, I checked the fit of my prototype to see how close we were. Of course, I also took a ton of pictures.

A Mother bear’s prints in the foreground and her cub’s prints in the background in the snow outside of Utqiagvik. Photo Credit: Elisabeth Kruger

After the zoo visit, while we were eating lunch, Elisabeth suggested I tag along when she headed up to Utqiagvik in two days so I could experience the Artic through a local lens. Because I was designing the tag not only to be low impact on the bears, but easy to use for the people installing it, this was an opportunity I couldn’t pass up. I quickly changed my plane tickets, went to REI to buy warmer clothes, and a day later hopped on the plane with Elisabeth. We were there to help a team of investigators - Micaela Hellstrom, a Swedish geneticist – Andy Von Duyke, a wildlife biologist with the North Slope Borough Department of Wildlife Management (NSBDWM) - collect the top layer of snow from bear prints. The bears leave behind tiny flakes of skin with each step they take and, using a technique she developed, Micaela is able to analyze the eDNA (environmental DNA) to passively identify individual bears that are crossing paths with humans. With local hunter and NSBDWM polar bear patrol manager Billy Adams and his shotgun as our guide and protection, we set off to see if we could find any bears. At first all we found were tracks, which was disappointing for me, but exactly what Micaela, Andy, and Elisabeth were after. During the sample collection process, I observed just how difficult it was to do anything dexterous with enormous gloves on, and how quickly your hands froze if you took them off, and all we were doing was scooping snow into plastic bags. It really reinforced that whatever attachment method I settled on had to be foolproof and fast.

In Utqiagvik, the sun doesn’t rise above the horizon from November 18th to January 23rd and “daylight” is more of an extended dusk. What little light we had was starting to fade to true dark at 3pm and we were about to head back when Billy spotted a bear in the distance. It wasn’t long before we realized it was a mother and her two cubs, but they had already noticed us and were on the move. Hopping on our snow machines we followed from a respectful distance until we hit the sea ice pressure ridges and the snow became impassible. At the furthest northern point in the United States, we stopped, collected more bear snow and then headed home. It had been a hell of a start to 2019 for me so far.

The silicone model of a polar bear ear and a 3D printer prototype showing size and fit.

The view from the inside of the ear showing the galvanic corroding release nut.

Back home in Reno I had everything I needed to finalize the tag’s physical package. I created a 3D model of a bear ear based on my measurements in combination with 3D scans we got from a zoo and worked with the incredible model shop crew at IDEO to make a silicone version. I worked with Misty West to reshape the circuit boards to hold the battery and antenna in a way that would cup the bear’s ear and prevent the device from rotating, a key aspect needed to keep the antenna pointed towards the sky. The physical ear model came in handy for checking shapes and experimenting with the post and corroding nut I’d worked on with Andre. After watching videos of bears fighting, hunting and swimming through ice flows and consulting with hunters from Utqiagvik and Nome, I realized that the best way to ensure that all the sensitive bits inside stayed safe and dry was to encapsulate the entire device. There aren’t many materials that are light weight, white (to blend in with the bears), super durable, resistant to cold and UV light and don’t interfere with radio waves. I realized I needed another expert and proceeded to contact Al Desito at Epoxies Etc. After I laid out what I was looking for, he narrowed it down to a few likely candidates and sent me samples of all of them.

Potting material tests that were made for evaluation.

Now I had to figure out how to hold all the little parts in place securely to be able to pour these materials over them in a process called potting. I designed a small 3D printed frame that all the pieces would be glued to and then, working once again with the guys from IDEO, we machined a two-part mold that would allow us to use a caulking gun to squeeze the potting material and cover the entire assembly. That was the plan at least. Things didn’t go smoothly on the first few tries. Some of the materials got too hot as they were curing and cracked the mold. Some of them were exceedingly sticky and they refused to come out of the mold no matter how much mold release spray we used on it. In the end, we landed on a urethane that had excellent material properties in the cold and was easy enough to work with. We finally had our first material representative prototype!

That’s when we realized it was too heavy. A few setbacks on sourcing the exact battery we’d wanted, combined with the fact that potting electronics just tends to be heavy, and we had blown our weight target. We took a step back and went back over all the decisions we’d made as a team to see where we might shave weight, but there wasn’t a lot we could do to lighten things even if we tore it up and started over. Fortunately, I remembered a technique from my time working with carbon fiber in college. When we encountered little holes in the race car parts we were making, we filled them with a mix of epoxy and a powder made of tiny little air-filled spheres of glass to help keep the weight down. We tried mixing the glass microspheres into the urethane potting material, and it worked marvelously, helping us shave off precious grams. The tag was still a bit heavy, but we were at least in the ballpark now.

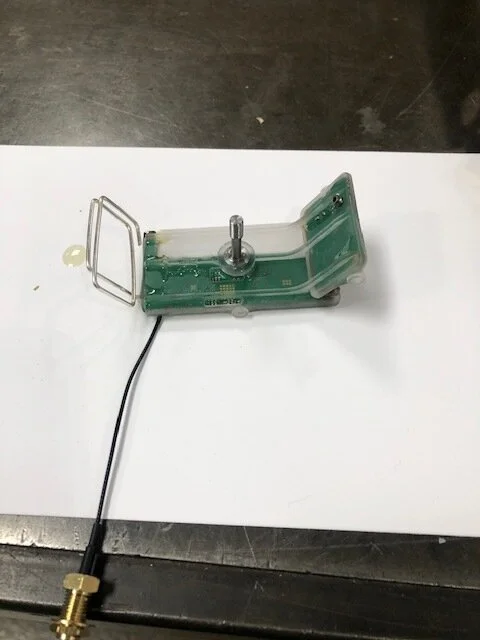

Antenna testing unit before potting.

Antenna testing unit after potting.

Around that time, Misty West noticed we weren’t getting the type of antenna performance we were hoping for. Radio antenna engineering is black magic, so Misty West turned to their hired antenna wizard, John Turner of Valhalla Systems. Working out of his home laboratory he helped the electrical team make tweaks to the circuit boards and worked with me to figure out if there were better shapes for the coils of wire that make up one end of the antenna. He discovered that those glass microspheres I mentioned earlier had inadvertently helped antenna performance and we tested how much we could add before the material started breaking down. Combining all the little improvements, we manufactured special prototypes with wires hanging out that would allow us to evaluate the antenna in an anechoic chamber to further refine the system and ensure that we would be able to communicate with the Argos satellites.

That’s where we find ourselves today; we are 95% of the way there but it’s always that last 5% that takes 30% of the effort. My work on this initial set of prototypes is largely over while I wait for John and the Misty West crew to eek out every bit of transmitting power and chase down all the little electrical and software gremlins. With limited funds, limited resources, and a limited number of the special microchips that talk to the satellites, we’ve got to make sure everything is working perfectly before we seal up the device: once its sealed, there is no recovering the electronics. The final step of putting the tags on bears is an expensive and bureaucratically challenging process as well, making it even more critical that we get everything right.

The (B)ear Tag project has been one of the highlights of my career. Not only has it provided endless dinner party stories, but it has pushed my boundaries as a mechanical designer. I’ve had to leverage all my experience from medical devices, race cars, consumer electronics and user research and combine it all. This has truly been a team passion project with people from all over the world contributing their expertise and their time and as a result I’ve met so many interesting, talented and brilliant people. I look forward to the day when we get our first pings from the satellites telling us a bear is on the move!